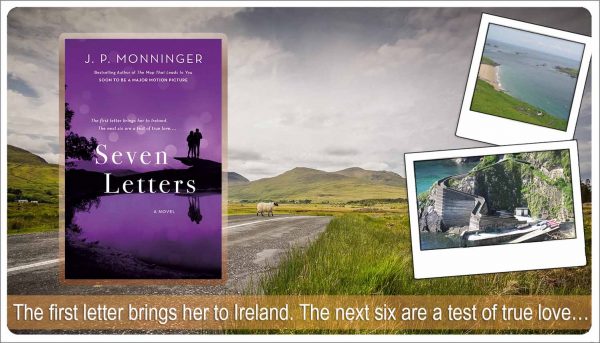

Title: Seven Letters (A Novel)

(A Novel)

Author: J. P. Monninger

Publisher: St. Martin’s Press

Genre: Women’s Fiction

Pub Date 08 October 2019

From the author of The Map That Leads to You comes another sweeping, romantic novel about love, family, and what it means to build a home together, SEVEN LETTERS (St. Martin’s Griffin; October 8, 2019, $16.99).

The Blasket Islands are the heart of Ireland – once populated with some of the most famous Irish writers, they are now abandoned, filled with nothing but wind and silence. Kate Moreton, a PhD student at Dartmouth, is in Ireland to research the history of the Blaskets, not to fall in love. She has a degree to finish and a life back in New Hampshire that she is reluctant to leave.

But fall in love she does, with both the wild, windswept landscape and with Ozzie, an Irish-American fisherman with a troubled past who shares her deep, aching love for the land. Together, they begin to build a life on the rocky Irish coast. But when tragedy strikes, leading Kate on a desperate search through Europe, the limits of their love and faith in each other will be tested.

Excerpt: Seven Letters by J.P. Monninger

PROLOGUE

The Irish tell a story of a man who fell in love with a fairy woman and went with her to live on an island lost to time and trouble.

They lived in a thatched cottage overlooking the sea with nothing but donkeys and gulls and white chickens to keep them company. They lived in the dream of all lovers, apart from the world, entire to themselves, their bed an island to be rediscovered each night.

In all seasons, they slept near a large round window and the ocean wind found them and played gently with their hair and carried the scent of open water to their nostrils. Each night he tucked himself around her and she, in turn, moved closer into his arms, and the seals sang, and their songs fell to the bottom of the sea where the shells held their voices and relinquished them only in violent storms.

One day the man went away, mortal as he was; he could not resist his longing to see the loved ones he had left behind. She warned him that he would grow old the moment his foot touched the soil of the Irish mainland, so he begged her for one of the donkeys to ride back to his home for a single glance at what he had left behind.

Though she knew the risk, she loved him too much to deny his wish, and so he left on a quiet night, his promise to come back to her cutting her ears with salt and bitterness. She watched him depart on a land bridge that arced to the mainland and then turned back to her cottage, knowing his fate, knowing that love must always have its own island.

She raised up the fog from the ocean and she extinguished all light from the island and the chickens went mute and the donkeys brayed into the chimney smoke and the gulls called out her anguish.

After many days of travel, and through no fault of his own, he touched ground and became an old man in one breath. Even as age claimed him upon the instant of his foot striking the soil, he called to her to save him, but she could not help him any longer.

In the seasons afterward, on certain full moon nights, she permitted the island to rise from the mist and to appear to him, or to any broken-hearted lover, the boil of the sea stilled for an unbearable glimpse of what had been lost so thoughtlessly.

To his great age he lived for the moments when he might hear her voice rising above the sea, the call of their bed and their nights and their love, the call of his heart, the call of the gulls that held all the pain of the world.

He answered on each occasion that he was here, waiting, his heart true and never wavering, his days filled with regret for breaking their spell and leaving the island. He asked her to forgive him the restlessness, which is the curse of men and the blood they cannot still, but whether she did or not, he could not say.

Chapter 1

I had misgivings: it was a tourist bus. As much as I didn’t want to admit it, I had booked passage on a tourist bus. It wasn’t even a good kind of tourist bus, if there is such a thing. It was a massive, absurd mountain of a machine, blue and white, with a front grill the size of a baseball backstop.

When the tour director—a competent, harried woman named Rosie—pointed me toward it with the corner of her clipboard, I tried to imagine there was some mistake. The idea that the place I had studied for years, the Blasket Islands off Ireland’s southwest coast, could be approached by such a vehicle, seemed sacrilegious.

The fierce Irish women in my dissertation would not have known what to say about a bus with televisions, tinted windows, air-conditioning, bathrooms, and a soundtrack playing a loop of sentimental Irish music featuring “Galway Bay” and “Danny Boy.”

Especially “Danny Boy.” It was like driving through the Louvre on a motor scooter. It didn’t even seem possible that the bus could fit the small, twisty roads of Dingle.

I took a deep breath and climbed aboard. My backpack whacked against the door.

Immediately I experienced that bus moment. Anyone who has ever taken a bus has experienced it. You step up and look around and you are searching for seats, but most of them are taken, and the bus is somewhat dimmer than the outside light, and the seat backs cover almost everything except the eyes and foreheads of the seated passengers.

Most of them try to avoid your eyes because they don’t want you sitting next to them, but they are aware, also, that there are only so many seats, so if they are going to surrender the place next to them they would prefer it be to someone who looks at least marginally sane.

Meanwhile, I tried to see over the seat backs to vacant places, also assessing who might be a decent, more or less silent traveling companion, while also determining who seemed too eager to have me beside her or him. I wanted to avoid that person at all costs.

That bus moment.

I also felt exhausted. I was exhausted from the Boston–Limerick flight, tired in the way only airports and plane air can make you feel. Like old, stale bread. Like bread left out to dry itself into turkey stuffing.

I felt, too, a little like crying.

Not now, I told myself. Then I started forward.

The passengers were old. My best friend, Milly, would have said that it wasn’t a polite thing to say or think, but I couldn’t help it.

With only their heads extending above the seat backs, they looked like a field of dandelion puffs. They smiled and made small talk with one another, clearly happy to be on vacation, and often they looked up and nodded to me. I could have been their granddaughter and that was okay with them.

They liked “Danny Boy.” They liked coming to Ireland; many of them had relatives here, I was certain. This was a homecoming of sorts, and I couldn’t be crabby about that, so I braced myself going down the aisle, my eyes doing the bus scan, which meant looking without staring, hoping without wishing.

Halfway down the bus, I came to an empty seat. Two empty seats. It didn’t seem possible. I stopped and tried not to swing around and hit anyone with my backpack. Rosie hadn’t boarded the bus; I could see the driver standing outside, a cup of coffee in one hand, a cigarette in the other. Two empty seats? It felt like a trap. It felt too good to be true.

“Back here, dear,” an older man called to me. “There’s a spot here. That seat is reserved. I don’t think you can sit there. At least no one has.”

I considered trying my luck, plunking down and waiting for whatever might happen. Then again, that could land me in an even more horrible situation. The older gentleman who called to me looked sane and reasonably groomed. I could do worse.

I smiled and hoisted my backpack and clunked down the aisle, hammering both sides until people raised their hands to fend me away.

“Here, I’ll just store this above us,” said the old man who had offered me a seat. He had the bin open above our spot. He shoved a mushroom-colored raincoat inside it. He smiled at me. He had a moustache as wide as a Band-Aid across his top lip.

I inched my way down the aisle until I stood beside him. “Gerry,” he said, holding out his hand. “What luck for me.

I get to sit next to a beautiful, red-haired colleen. What’s your name?”

“Kate,” I said.

“That’s a good Irish name. Are you Irish?”

“American, but yes. Irish ancestry.”

“So am I. I believe everyone on the bus has some connection to the old sod. I’d put money on it.”

He won a point for the first mention of the old sod that I had heard since landing in Ireland four hours before.

He helped me swing my bag up into the bin. Then I remembered I needed my books and I had to swing the backpack down again.

As I dug through the bag, Gerry beside me, I felt the miles of traveling clinging to me. How strange to wake up in Boston and end up on a bus going to Dingle, the most beautiful peninsula in the world.

Published with permission. Copyright J.P. Monninger. Montlake.